Historical and Cultural Aspects

The breasts, unlike most other organs, have been a visible structure ever since the birth and evolution of the mammal. Although they have run the gamut of religious, psychological, and erotic environments in history, the study of its internal structure seems to have arrived relatively late.

The breast was viewed as sacred (especially pre-1400), erotic (Renaissance and thereafter), political (French Revolution), psychological (as in Freud’s obsession), and medical (including breast cancer and cosmetic surgery).

MatthiasKabel – Own work

Venus of Willendorf is a figurine from 25,000 BC one of the earliest sculptures of the female form. She is believed to have represented a goddess and is characterised by large breasts, abdomen, buttock and pubic area

Figurine seen from four sides

Bjørn Christian Tørrissen –

A figure with similar proportions The Venus of Lespugue, c. 30,000 BCE is also considered a deity and may even predate Venus of Willendorf.

The Venus of Lespugue is a prehistoric figurine dating back to the Upper Paleolithic period. It was discovered in 1922 in the Lespugue Cave in southwestern France. The figurine is made of mammoth ivory and is approximately 6 inches (15 centimeters) tall. It is considered one of the most famous and important examples of Paleolithic art.

The Venus of Lespugue is notable for its exaggerated female attributes. It depicts a woman with prominent buttocks and breasts, a small head, and no visible face. The figure’s arms are folded and rest on her stomach. The exaggerated features suggest that the figurine may have represented fertility or played a role in rituals related to reproduction and childbirth.

The Venus of Lespugue is part of a larger tradition of prehistoric female figurines found throughout Europe, known as Venus figurines. These figurines are often associated with fertility, as many of them emphasize the female reproductive features. The Venus of Lespugue is particularly well-preserved and showcases the artistic skills and cultural symbolism of the people who created it.

Today, the Venus of Lespugue is housed in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, France. It remains an important artifact in the study of prehistoric art and provides valuable insights into the cultural and artistic practices of our ancient ancestors.

Vassil – Own work

In the Minoan culture of ancient Crete, there is a prominent figure known as the Snake Goddess. The Snake Goddess is depicted in various forms of art, primarily in the form of statuettes and frescoes, and is often associated with religious or ceremonial practices.

The Snake Goddess is typically represented as a female figure holding or accompanied by snakes. She is depicted wearing an elaborate headdress and a long, flounced skirt. In some depictions, she is shown with her arms raised, holding snakes in each hand, while in others, she is shown with snakes coiling around her arms or neck. The presence of snakes suggests a connection to nature, fertility, and potentially even a symbol of the underworld.

The exact role and significance of the Snake Goddess in Minoan culture are not fully understood. Some theories suggest that she represented a powerful deity associated with fertility, nature, and rebirth. Others propose that she may have been a priestess or a representation of a high-ranking female figure within Minoan society.

The Snake Goddess is often associated with the religious practices of the Minoans, who worshiped a pantheon of deities and engaged in rituals and ceremonies. Snakes were considered sacred creatures in many ancient cultures and were often associated with healing, transformation, and the powers of the earth.

The Minoan Snake Goddess remains an intriguing and enigmatic figure in ancient art and mythology. The archaeological discoveries of Minoan sites, such as the Palace of Knossos, have provided valuable insights into the vibrant and complex civilization that thrived on the island of Crete during the Bronze Age.

Wiki Courtesy C messier – Own work

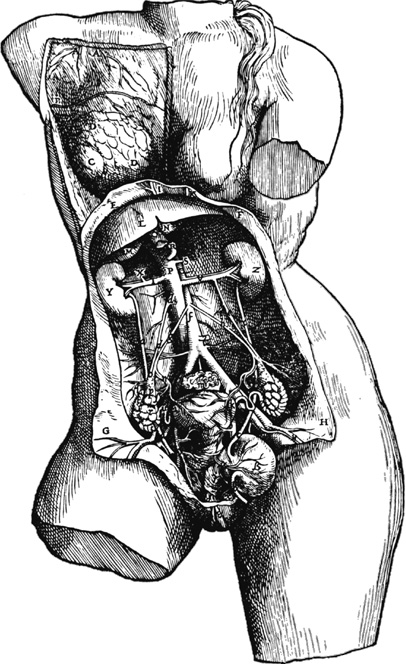

Andreas Vesalius’ “De humani corporis fabrica libri septem” (often referred to as “Fabrica”) is a groundbreaking anatomical work published in 1543. While the primary focus of the book is the study of human anatomy as a whole, it also includes depictions of the female form and reproductive system.

In “Fabrica,” Vesalius aimed to provide a comprehensive and accurate understanding of the human body based on his dissections and observations. The book challenged the prevailing knowledge and teachings of the time, including those of Galen, a prominent physician and anatomist whose ideas had been accepted for centuries.

Regarding the female form, Vesalius dedicated a section of “Fabrica” to the reproductive system. He depicted the female pelvis, uterus, and other reproductive organs in detail, aiming to provide an accurate portrayal of their structure and function. Vesalius’ illustrations were based on his direct observations during dissections and represented a significant advancement in anatomical knowledge.

The inclusion of the female form in “Fabrica” reflects Vesalius’ comprehensive approach to the study of human anatomy. While the focus of the book was not specifically on the female body, Vesalius recognized the importance of understanding both male and female anatomy in the pursuit of medical knowledge.

“Fabrica” revolutionized the field of anatomy and had a profound impact on the study of medicine. Vesalius’ emphasis on direct observation, meticulous illustrations, and critical analysis of previous anatomical teachings laid the foundation for modern anatomical studies. His work marked a shift towards a more empirical and evidence-based approach to understanding the human body, which has continued to shape medical education and research to this day.

Public Domain

Vesalius’s drawings of anatomy in “De Corporis Humani Fabrica” of 1543 reveal one of the earliest interests in the internal structure. Da Vinci on the other hand, who demonstrated such in-depth probing of the anatomy, has no established drawings of the dissected breast.